In its heyday, Curtin was quite the place. Well-heeled relations, friends, and acquaintances of the Curtins often traveled to and from Curtin by rail. The Curtins had a set day of the week to receive visitors. In turn, the Curtin women would go to Bellefonte to visit or shop, but they were also well-traveled – to Philadelphia, New York, the West, or international destinations.. Here, an undated and uncaptioned photo from the Curtin Mansion Archives shows a stylish woman and several others at the railroad station. The styles would have been in vogue 1902-1908. Make your own Curtin history. Come for a tour of Eagle Iron Works and Curtin Village by train on Sunday July 7. The Bellefonte Historical Railroad Society will operate excursions, departing from Bellefonte’s Talleyrand Park for a 30-minute ride to Curtin and returning to Bellefonte after a one-hour stay. Details, departure times and tickets are available at bellefontetrain.org

0 Comments

In his authoritative book, Making Iron on the Bald Eagle (ref 1), the late Penn State Emeritus History Professor Gerald Eggert stated that both Roland Curtin (b. 1764) and his brother Constans (b.1783) received a quality primary education and that both attended O’Halloran’s Classical School in Ennis, near their home in Dysert, County Clare, Ireland. To support this assertion, Eggert cited two secondary sources: the first, an account by Dr Roland G Curtin, Roland Curtin’s nephew (Constans Curtin’s son) in “Genealogy of the Curtin Family”, accessible in the Centre County Historical Library, Bellefonte, PA; the second, a letter from George Potter Curtin to “Aunt Kas”, dated March 17, 1984, accessible in the Curtin Mansion Archives.

Roland and Constans’s parents, being Catholics, would have encountered difficulties in securing a quality education for their children. A series of Penal Laws in 17th and 18th century Ireland were designed to prohibit Catholics from teaching school and also to prevent Catholic parents from circumventing the law by sending their children to study abroad (ref 2 and 3). The Education Act of 1695, for example, stated: “teaching by Papists is one great reason that many natives are ignorant of the principles of true religion” [Anglican]. With a fine of 20 pounds and three months in prison for each offence, teachers who broke these laws put themselves at considerable risk. During the era of the Penal Laws, many Catholic children were deprived of even primary education. There were public schools in some places, and in fact some Catholics chose to enroll their children. A grammar school was set up in Ennis in 1773, for example, and in 1778, there were 80 students, six of whom were registered as Catholics (ref 4). It also was common during these years that independent Catholic teachers, often itinerants, defied Parliament (ref 4). They were surreptitiously paid to hold classes in ‘hedge schools’, although the schools were commonly in barns or houses, not in the open air next to hedgerows as might be inferred from the name. After the repeal of the 1695 Education Act in 1782, Catholic teachers publicly advertised their services. One well-known area Catholic teacher, who perhaps emerged from the hedges, was Stephen O’Halloran. He taught at the Ennis Grammar School (ref 5), presumably after 1782, when the infamous Education Act of 1695 was repealed. O’Halloran’s Classical Academy was founded in 1792, endured, and became known for preparing students to attend the Catholic seminary at Maynooth, founded three years later, in 1795 (ref 6). It is possible that Roland Curtin was under Stephen’s tutelage during the era of hedge schools, or that Roland attended the public grammar school in Ennis. Roland would have already have been 17 or 18 when the Education Act was repealed (after which time Stephen O’Halloran could have taught legally at the public school), however, and 27 or 28 when the academy was established on O’Connell Street. It seems more likely that Constans and one or more of Roland’s other younger brothers were taught by Mr. O’Halloran at the public school or attended his academy. References: 1. Eggert, G G. Making Iron on the Bald Eagle, Penn State University Press, University Park, PA, 2000, p8. 2. Education Act 1695, Online at Wikipedia 3. Penal Laws (Ireland), Online at Wikipedia 4. Power, J. Education in Claire. Online at clairelibrary.ie 5. Ó Dálaigh. Tomás Ó Míocháin and the Munster Courts of Gaelic Poetry, c 1730-1804, Eighteenth-Century Ireland Society (https://www.stor.org/stable/24389561) 6. Ó Dálaigh, B. Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no 25, Ennis, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 2012 (www.ihta.ie, accessed June 29, 2024), text, p 6 Katharine Irvine Wilson (1821-1903) married Andrew Gregg Curtin (1815-1894) on May 29, 1844. She was the daughter of a country doctor, Dr William Irvine Wilson (1793-1883) and Mary Potter Wilson (1798-1861). At first glance, it might seem that a young woman residing in the countryside of mid-19th-century rural Pennsylvania would be an unlikely match for the up-and-coming scion of the prominent Curtin Family. This was far from the whole story, however, and indeed the families of Andrew and Katherine had a long-standing association, and both were families of distinction. Katahrine's mother, Mary Potter Wilson, was the daughter of General Judge James Potter (1767-1818). Katharine's great-grandfather was Revolutionary War Colonel -- then Brigadier General -- James Potter (1729-1789), an Irish immigrant who had arrived in America in 1741. As a captain in the provincial army circa 1759, he explored the region, entering via the West Branch of the Susquehanna to Bald Eagle Creek to Spring Creek, and then reputedly became the first European to view Penn's Valley. Years later, after a distinguished military career in the Pennsylvania Militia, he served briefly as Vice President of Pennsylvania (1781-82). He found his contentment, however, in establishing a farm and a grist mill, around which arose the community that is still known as Potters Mills.

Andrew Gregg Curtin's parents were Roland Curtin (1764-1850), the Irish immigrant who was the founding patriarch of the Curtin iron-making enterprise, and Jane Gregg Curtin (1791-1854). Jane's parents were US Congressman, later US Senator Andrew Gregg (1755-1835) and Martha Potter Gregg (1769-1815). Martha Potter Gregg was General Judge James Potter's sister. Accordingly, Andrew Gregg Curtin's maternal grandmother was the sister of Katherine Irvine Wilson's maternal grandfather. In other words, Andrew and Katharine had great-grandparents in common -- James Potter and Mary Patterson Chambers Potter -- meaning the bride and groom were second cousins. By all accounts, the comely and affable Katherine and the handsome and affable Andrew were well-matched. Katharine became the First Lady of Pennsylvania from 1861 to 1867 and received many dignitaries, among them President-Elect Abraham Lincoln en route to his inauguration; accompanied Andrew and at least two of their five children when Andrew was Minister (Ambassador) to Russia from 1869-1872; returned to their home in Bellefonte prior to Andrew's three terms in the US Congress; remained married to Andrew for 50 years, until his death in 1894. On December 7, 1903, Katherine was stricken at lunchtime by "a stroke of apoplexy" after she returned home from shopping and died within an hour. She is buried in Union Cemetery, Bellefonte. There is an additional footnote with a touch of humor. Roland Curtin (1764-1850) married his first wife, Margery Gregg Curtin (1780-1813) in 1800. Roland Curtin's brother, Dr. Constans Curtin (1783-1842), married Margery's first cousin, Martha Gregg (1793-1829) in 1810. A year after the death of Roland Curtin's first wife Margery in 1813, Roland married Jane Gregg (1791-1854), the sister of his brother's wife, Martha. So by the time Andrew married Katharine in 1844, the Curtins, the Greggs, and the Potters had been intertwined for more than 40 years. Even if you are paying close attention, you might need to draw a diagram. References: 1 - Online: Find a Grave: Katharine Irvine Wilson Curtin; Mary Potter Wilson; General Judge James Potter; James Potter: Jane Gregg Curtin; Martha Potter Gregg. 2 - Lowrie, SD: Katharine Irvine Wilson Curtin. In: Notable Woman of Pennsylvania, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2016. 3 - Eggert, G: Making Iron on the Bald Eagle, p 3. Penn State University Press, University Park, 2000. While giving tours at Curtin, more than once I have been asked to explain the mechanics at work inside the blast house. I’m not a mechanic or an engineer, so this explanation is geared to those of us lacking such expertise. In a charcoal-fired iron-producing blast furnace there was a constant stream of air pumped across the charcoal at the base of the furnace. We’ve all seen how a bellows works to heat up a fire. Smelting iron requires the furnace to reach about 2800ºF, and the bellows effect is necessary to heat the charcoal sufficiently. In fact, that “blast”of air is what gives a blast furnace its name and why there is a structure known as the blast house. Below is a diagram of the mechanics inside the blast house. A flume carried water flowing from nearby Antes Creek, now called Nittany Creek. The water powered a water wheel, which in turn moved two reciprocating piston rods, one on each side of the waterwheel, up and down. (Reciprocating just means it moves up and down, as opposed to making a rotary motion.) Attached to the top of each piston rod was a metal crown with a one-way valve in its middle. As the piston rod rose, it powered the metal crown upward inside the piston cylinder, and the valve closed. Air was thereby compressed inside the piston cylinder and forced into the adjacent mixing box. As the waterwheel continued turning, the piston rod and the attached crown moved back down. When the piston crown started its descent, a second valve at the top of the piston cylinder closed, preventing the compressed air in the mixing box from re-entering the piston cylinder. Simultaneously, as the piston crown was pulled down, the valve at its center (that had been closed on the way up) opened, allowing the next gulp of air to enter the cylinder from outside. In synchrony, the piston rod and metal crown on the opposite side of the waterwheel was moving upward as the piston rod and metal crown on the first side were moving downward. Valves on the second side similarly controlled the direction of airflow into the mixing box and prevented air from moving back into the piston cylinder. As air was pushed into the mixing box from side two, the valve at the top of the piston cylinder on side one closed.

Since the two pistons worked in synchrony, and two valves on each side regulated air movement, the compressed air in the mixing box could only move in one direction, outward through the air duct leading to the tuyere at the base of the furnace. (Tuyere is a word borrowed from the French word meaning nozzle and is pronounced in English something like twee-air.) The air pressure inside the mixing box was only about one pound per square inch, but it was enough to move the air forward into the furnace and get the job done. Note — For purposes of clarity, I’ve drawn the analogy to pistons in a car engine. In reality, what I’ve called piston cylinders in the diagram and description were fairly air-tight, leather-lined barrels called blowing tubs. The mechanics are the same. Reference: Eggert, GC, Making Iron on the Bald Eagle, Penn State University Press, 2000 While starting a project at Curtin this past week, I was reminded of the way my dad rarely discarded anything. In fact, it went beyond that. He loved to roam junk yards, searching for a specific item he wanted, or just looking around for something that piqued his interest. Anything from rusty tools, to defunct small motors, to antiquated cars were his quarry. His treasures might be so old as to require carbon dating to determine their age, but Walter Glenn dismantled, cleaned, tinkered, and willed ancient objects back to life.

Recently, Phil Ruth, fellow board member of the Roland Curtin Foundation and our vice-president, decided to upgrade signage around Eagle Iron Works and Curtin Village. He designed and obtained new signs to help the many folks who take self-guided tours of our site. In the Curtin tradition, instead of buying new sign posts, he decided to uproot and refurbish the existing ones. I volunteered to help with the refurbishing phase of the large project. Parenthetically, there are endless projects at Curtin that are begging for volunteers to jump in and help us preserve history. But I digress … Nine posts were needed for the new signs. The first step, of course, was surface preparation, and there indeed was a lot of preparation to do. Phil had brought a variety of scrapers, brushes, and sanders. I propped the nine posts on the side of the barn and set four of them on sawhorses. It was 9:45. The first post… There were plenty of problem spots, most severe at the point where it had entered the ground. I scraped by hand the big bits of dried dirt and loose debris, and then used a wire brush to clean out ruts and holes. I started up the power sander. A quick once-over was not bringing it up to a standard needed for refinishing. I directed attention to small areas, going round and round, varying the pressure applied. Bit by bit, a nice smooth, clean surface emerged, ready for a new coat of stain. After a time, my hand cramped up and my mouth was parched, so I paused to survey progress. I had completed one quarter of the first of four sides of the first post. That didn’t include the four-facet pyramidal post cap, nor the bottom. It was 10:45. It called to mind something that happened when I was about 12. It was Spring, and I wanted a new bike. My dad said that my older brother’s bike – he was 12 years older and had already gone off to the Far East in the Army -- was in the cellar, and it could be mine. I pulled it out into the backyard. It was beat up, the tires were flat, and the wheel rims and frame were rusted. You’ve got to be kidding, I told my dad that it was a complete mess, and he said something like, “Well, you can fix that, and it will be just fine.” He handed me sandpaper and a wire brush and left me to it. I spent a couple hours trying to get the wheel rims looking acceptable. You realize how hard it is to get any leverage between spokes, and the wire brush dealt out any number of scrapes and punctures in the process. I had made a little progress, but the chrome was still pock-marked and dingy. My dad reappeared and said something like, “No, that won’t do.” He took the wire brush and chips flew. Then, he went round and round with sandpaper, working for a full several minutes on an area of about one square centimeter. The tip of his tongue appeared at the corner of his mouth. That always happened when he was concentrating. It looked fine to me, but he wasn’t satisfied. He applied silver polish and went over the same bit again and again. About ten minutes and two more applications of polish later, that one tiny section was completely clear. It shined, as if brand new. “There,” he said, “that’s what I have in mind.” And by the end of summer, I had a shiny “new” bike. ********* Walter Glenn was born in Curtin in 1905. His father, Jeremiah, was also born in Curtin in 1874 and was the company storekeeper and village postmaster from about 1901 until the iron company folded in 1922. Walter’s mother, Rebecca, was born elsewhere in 1876, but came to Curtin as a girl, the daughter of the previous storekeeper and postmaster, John Parker. Rebecca found time to help Jeremiah in the store in addition to tending their house and preparing the meals; birthing eleven babies; raising the nine children who survived infancy; planting, harvesting, and processing a huge garden. In later life, she lived independently for 27 years as a widow after Jeremiah died at age 62. I can remember Rebecca scrubbing pots and pans with a round and round motion until they shined, as if brand new.  Iron Works Wednesday, January 24, 2024 -- Curtin Methodist Church and Cemetery. Location 305 Curtin Road, Howard, PA 16841 (Published on our FACEBOOK page every Wednesday. Visit Facebook for more photos.) The Methodist Church at Curtin has a very long and distinguished history. By 1787, six members of its earliest congregation met as a Methodist “class” in the nearby log home of Philip and Susanna Antes. These six members were: Philip Antes and wife, John S. Bathurst and wife, and Christopher Helford and wife. By 1791, circuit riders preaching the gospel came every two weeks, and in 1792 this small congregation, which in the coming years would include other familiar names such as Barnhart, Lee, Miller, Lipton, Jacobs, Holt, and Watkins, received its first pastor. On January 21, 1806, Philip Antes and his wife, deeded one-fourth of an acre of ground to six persons who served as trustees, Richard Gonsalus, Frederick Antes, William Forester, Lawrence Bathurst, Abel Daugherty, and Philip Antes, in trust to erect a house of worship. In addition to these individuals, other members of the church were Christopher Helford, Philip Barnhart, Jacob Lee and their families. Early church records indicate that construction of the “Bald Eagle Chapel” actually began in 1804 prior to receiving the deed for the land, and dedication of the building occurred one year later in 1805. Based on written accounts, it appears that the building was of log construction with one double entrance door and five windows containing 101 panes of glass. By 1810, Roland Curtin Sr. and Moses Boggs had established Eagle Forge along Bald Eagle Creek downstream of Philip Antes’ Gristmill. Soon after, just a short distance south of “Bald Eagle Chapel”, Curtin added Eagle Furnace in 1818 and a rolling mill to his expanding operation in 1830. By then Philip Antes had moved further west to Clearfield County and sold his land to Roland Curtin permitting further expansion of the Eagle Iron Works to include a Workers’ Village, boarding house, a large, 1831, Federal-style mansion, Pleasant Furnace in 1848, a company store, and a circa 1870 manager’s house. By 1865, this bustling community was serviced by The Bald Eagle Valley Railroad that extended from Tyrone to Lock Haven and a passenger and freight station was constructed. No doubt the increasing population of Curtin Village contributed toward the need for a larger house of worship beyond what the 1805 log church could serve. The present-day Curtin Methodist Church was dedicated in 1872 and continues to serve its Methodist congregation 237 years after those early beginnings. Church services are held every Sunday. Old Curtin Cemetery, also known as United Methodist Cemetery, was founded in conjunction with the church. It contains 134 known burials; the oldest of which appears to be 1815 for the infant grandson of Philip and Susanna Antes. However, of the surviving stones, there are few prior to the 1850s. Of the nearly 200 Revolutionary War soldiers buried in Centre County, two find their resting place here, Lawrence Bathurst (1757-1845) and Evan Russell (1760-1838). The monument in front of the cemetery reads, "In memory of Philip and Susanna Antes, in whose log cabin near here, the first Methodist Episcopal Society in the Territory of Centre County, of the Little York and Juniata Circuit, was formed July 1787 by Rev. David Combs, Circuit Rider. Erected by Friends and authorized by the Pennsylvania Historical Commission." The location of Antes Mill, now gone, is recognized on the Eagle Iron Works and Curtin Village Self-Guided Walking Tour, available adjacent to the parking lot in front of the Roland Curtin Mansion, 251 Curtin Road. The site is open year-round, dawn to dusk, for self-guided tours. Online donations are appreciated for the preservation of Eagle Iron Works and Curtin Village at www.curtinvillage.com. Sources: Berkheimer, Charles, F. “The Origin of Bald Eagle Chapel”, an address delivered August 18, 1963, at the Curtin Methodist Church Homecoming Celebration. Various church members who contributed footnotes and addenda to the 1963 speech include: Rev. Almon D. Baird, Mrs. Mary Shultz, Mrs. Stewart Pletcher and Mrs. Edgar Stitt. Linn, John Blair. History of Centre and Clinton Counties, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1883. Find-A-Grave Curtin Cemetery in Curtin, Pennsylvania - Find a Grave Cemetery Stover, Nancy. “Centre County American Revolutionary Soldiers and Patriots”. Centre County PAGen Web Project Centre Co. (PAGenWeb), PA.---American Revolution Soldiers & Patriots Andrew Gregg Curtin (AGC) was Roland Curtin’s first son by his second wife, Jane Gregg Curtin. Andrew had a distinguished career as an attorney, two-time governor of Pennsylvania and key Lincoln ally, minister to Russia, and three-term US congressman. Did you know, however, that before he won the governor’s office, AGC fell just one vote short of being elected to the US Senate? It’s true, and in fact there was quite a controversy about that election in 1855.

It was not the first time that electing a US senator stirred up trouble in Pennsylvania. Adopted in 1913, the 17th Amendment to the US Constitution determined that US senators were elected by popular vote, but before this uniform system was put in place throughout the country, senators were chosen by the State legislatures. Unfortunately, the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1790 was ambiguous concerning procedures. It was unclear if a candidate required a majority in each house of the legislature, or if the winner would require a majority of a joint meeting of both houses of the legislature. There was a deadlock over this question straightaway in 1791. Pennsylvania had only one sitting US Senator until the issue was resolved two years later in favor of requiring a majority vote of the joint legislature. So it was in early 1855 when Simon Cameron and Andrew Gregg Curtin both sought election to the US Senate. Cameron, ever the wheeler-dealer, lobbied heavily to drum up enough votes among an unlikely coalition of factions. AGC at the time was a traditional member of the Whig Party. Cameron won the election by a single vote. Someone quickly realized, however, that the number of ballots cast outnumbered the number of legislators present. Chaos ensued, and the dispute was not resolved easily. Cameron was publicly accused of bribery. The controversy persisted for months, and Pennsylvania again had a single US senator until October, 1855. By then, control of the legislature had changed and a third person, ex-Governor Bigler, was sent to Washington. Cameron and AGC became bitter political enemies, and probably intensely disliked each other on a personal level. They clashed frequently during the Civil War, when Cameron was Secretary of War and AGC’s interactions with the War Department were frequent and strained. Lincoln had to act as peacemaker and arbiter on more than one occasion. Reference -- Klein PS and Hoogenboom A: A History of Pennsylvania 2nd Edition, Penn State University Press, University Park, 1980 pp 114-115; pp 168-169. Anyone with an interest in the history of Curtin Village and the Curtin family knows the name of Andrew Gregg Curtin, founder Roland Curtin's son and Governor of Pennsylvania during the Civil War. Governor Curtin was not the only Curtin to make a name for himself, however. My favorite Curtin descendant is Roland Curtin's great-great grandson, Hoyt Curtin (1922-2000).

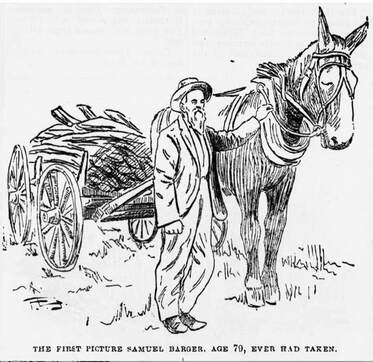

Hoyt Curtin was a descendant of founder Roland Curtin (1764-1850) via his son Roland G. Curtin (1808-1875), the Governor's half brother. (Roland G's mother was Margery Gregg Curtin; Andrew's mother was Margery's cousin, Jane Gregg Curtin.) Roland G. Curtin's grandson, Frank Montgomery Curtin (1880-1958) was born in Bellefonte, but migrated to California. Frank's son, Hoyt, was born there in 1922. Hoyt grew up in San Bernadino, CA and was interested in music from an early age. After serving in the Navy during WWII, he studied music at USC and landed a job composing music for radio and TV ads. His big break came when he worked with William Hanna and Joseph Barbera on a Schlitz beer ad. Hanna and Barbera were in the process of creating the Ruff & Ready cartoon show, and they asked Curtin to write a theme song. The legend is that Curtin presented them with a tune five minutes after being asked. Apparently it was exactly what they had in mind. Hanna and Barbera went on to become cartoon gurus, and Curtin became their music composer, arranger, conductor, and producer for more than 20 years. Without knowing it, those of us of 1950's vintage grew up listening to Hoyt Curtin's music. He created moods with the theme songs and background music for classics such as Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, Quickdraw McGraw, and Scooby Doo. Even the teenagers of today are familiar with the Jetsons and the biggest of all in my mind -- The Flintstones theme song. Most of us can play that theme in our mind and see Fred Flintsone peddling his car through Bedrock at the front end of the show and pounding on the front door of his house at the closing. But to appreciate Hoyt Curtin's genius, go back and listen to the brilliant brassy jazz in a lot of those pieces. It's interesting that the connection of this music to the Curtin legacy is a well-kept secret. My father was born in Curtin in 1905 and watched those shows with me when I was a little guy. I'm quite confident that he was unaware of the Curtin connection; otherwise, it is a near-certainty that he would have proudly pointed it out.  Terms that have been used to describe just the ordinary people of Curtin are dogged, fiercely independent, rugged, tough as nails. I search for an apt way to refer to Nancy Agnes (Tate) Barger. Thanks to Roland Curtin Foundation Board Member Phil Ruth for calling attention to an 1895 newspaper article (Ref 1) about Grandma Barger. Born in Cumberland County on Sep 14, 1791 according to this article – several other accounts and her obituary cite Sep 17, 1792 as her date of birth -- she was the fourth of 10 children of William and Rebecca Tate. She fell for George Barger, and in spite of disapproving parents, ran off and married him when George returned from serving in the War of 1812. George was a forgeman, and he was recruited by the Valentines of Chester County to move to Centre County to work in their new iron business soon after the conflict ended. George, Nancy, and their infant son Samuel made a three-week wagon journey to Centre County and settled first in or near Bellefonte. [The date of the journey indicated in the article was 1812, but their oldest son wasn’t born until 1816, give or take a year. Either the date of the trip or the son’s age given in the article is wrong; otherwise, Baby Samuel was not along for the ride.] In 1820, Roland Curtin hired George. Apparently, after working for Mr Curtin for a time, George moved his family to Mill Hall in order to labor at another forge. The Bargers settled permanently back at Curtin, then known as Roland, in or around 1832. George died in 1852, survived by Nancy and seven grown children. At the time of the 1895 article, Nancy would have already been a mature 103, give or take a year. She is described as having her faculties and being remarkably functional. She was seated by a crackling fire and eagerly posed for a photo. She regaled the interviewer with stories drawn from her long life. She recounted that she was away the day that convicted murderer James Monks was hanged in Bellefonte [at a public execution on January 23, 1819]. When she returned home, however, she heard from her husband about all the excitement the event engendered.  She indicated that four sons fought in the Civil War. John was killed, but three returned home. Her oldest son, Samuel, never was called into duty. He remained at home to look after his mother and sisters. Samuel never married, and in fact remained his mother’s provider and care giver in her last years. His picture is reproduced in the same article, appearing to be a sprightly 79, hauling firewood, perhaps, with the help of his mule. An article later the same year cites Nancy’s memories of Judge Charles Huston (1771-1849), PA Supreme Court Judge appointed in 1826 (Ref 2). Judge Huston had lived nearby and had told her about the excitement of joining the militia as troops marched through Carlisle on the way to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794. The day the newspaperman interviewed Nancy for this article, she got on her knees to pray with a visiting parson and was able to get back to her feet with surprising agility. Nancy “Grandma” Barger’s life ended in 1898 at 106 years, 1 month, 14 days, but she was a determined tough old bird and had survived an astonishing two months after breaking her hip in a fall (Ref 3) The article amusingly relates, “She was a free user of tobacco so far as smoking was concerned.” On a personal note, it is fascinating to me that my grandparents, Curtinites Jeremiah (1874-1936) and Rebecca Parker Glenn (1876-1963); my great-grandparents Andrew Curtin Glenn (1834-1902) and Rachel Aikey Glenn (1849-1927); and, for that matter, my great-great grandparents Jeremiah Glenn (1791-1876) and Margaret Curtin Glenn (ca 1808- ca 1875), who immigrated from Ireland and settled in Roland (Curtin) in 1831, would certainly all have known Nancy Barger and her family. In fact, the Bargers returned to Roland from their stint in Mill Hall shortly after my great-great grandparents arrived. I wonder if they were friends. References: 1 – Meek, GR: A remarkable old woman who lives with her 79-year-old son at Curtin’s Works. “Democratic Watchman”, 7 Jun 1895. 2 – Remarkably old woman. Mrs Nancy Barger of Roland, Centre County, over 104. Altoona Tribune, 30 Dec, 1895. 3 – Centre centenarian dead. The Times (State College), 3 Nov 1898 It's difficult to fathom that there were many bloody conflicts between Native Americans and European settlers in Central Pennsylvania less than 20 years before Roland Curtin arrived in the Bald Eagle Valley in 1797.

In fact, tales of brutal attacks involve Woapalanee (meaning Bald Eagle), a Delaware Chief in the Muncee tribe, for whom Bald Eagle Mountain, Creek, and Valley are named. An important east-west trail ran along the West Branch of the Susquehanna, up what is now known as Bald Eagle Creek, and from there to Snow Shoe, Clearfield, Punxsutawney, and Kittaning. Woapalanee traveled along the length of this trail and settled for a brief time at the confluence of Logan Branch and Bald Eagle Creek, near present day Milesburg. (Logan Branch may be named for Chief Logan, born Tah-gah-jute ca. 1723 near current day Sunbury. He was son of the Iroquois Chief Shikellemus, or Shikellamy.) On August 8th, 1778, militiamen were guarding harvesters at Smith's Farm, on Turkey Run, near Wiliamsport. Protection was necessary, because Peter Smith's wife and four children had been killed by Natives about a month earlier. Allegedly, on that August morning, Woapalanee was among attackers who killed a number of the farm workers and their guards. One militiaman of note, James Brady, was shot, struck with a tomahawk, and scalped (he had long red hair). Amazingly, he regained consciousness and staggered to a nearby cabin belonging to Jerome Vaness. Vaness bandaged his wounds and got word of the attack to Frot Muncy. A party of men fetched Brady and took him to Sunbury, where his mother was residing. James survived for five days*, long enough to relate the harrowing events and identify Woapalanee, known to him previously, as one of the attackers. Brady's brother Samuel vowed revenge, Revenge may have been satisfied less than a year later. By one account, Woapalanee was killed in June, 1779 on the Allegheny River, near the mouth of Red Bank Creek, fifteen miles north of Kittaning. (a large bend on the Allegheny near the spot is now known as Brady Bend.) Captain Samuel Brady commanded a party of about 20 men searching for Natives thought responsible for tomahawking a Mrs Frederick Henry, bashing the head of her baby against a maple tree, and taking serval other children hostage. (An older child escaped to hide in a cornfield and as able to describe events). The militiamen came upon a band of Natives and killed them. Among the dead was Woapalanee.** If the hills around Curtin could talk ... ______________ * Truly amazing, since scalp wounds bleed profusely. I saw many people with far less grievous wounds require aggressive infusion of fluids or blood to get them out of shock. That he survived being shot, bashed with a tomahawk, and scalped taxes credulity. ** A less believable legend is that Woapalanee was killed by three hunters and floated down the Monongahela propped in a canoe with a cigar in his mouth (or stuffed with journey-cake).. Only after floating downstream for a distance was the canoe run aground and discovered by a Mrs. Province. |

Jerry GlennJerry is a retired general surgeon and a new Board Member of the Roland Curtin Foundation. He has Curtin roots extending back to 1831, through four previous generations. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed